January in schools has a distinctive texture.

The break ends, the building wakes up, and the momentum returns quickly — sometimes faster than we feel ready for. In the space of a few days you’re back into routines, behaviour patterns, curriculum pacing, staff capacity, parent communication, meetings, deadlines… and that familiar sense of “we’ve got a lot to carry” comes rushing back.

For many leaders and teachers, the pressure isn’t just workload. It’s the mental load of trying to make good decisions while holding too many moving parts in your head at once.

That’s why this point in the year is a good moment to talk about clear thinking. Not as a fluffy idea, but as a practical form of relief.

Because when you can see what’s really going on — and why — progress becomes more likely… and the work becomes less stressful to carry.

The real January challenge isn’t effort — it’s fog

Most schools aren’t short on effort.

What’s harder is knowing whether effort is translating into improvement. You can be doing all the right things and still feel slightly unsure:

- Are we focusing on what matters most?

- Are we making progress, or just keeping afloat?

- Why do some priorities move while others stall?

- What’s actually getting in the way?

When those questions are unanswered, your brain keeps running them in the background. That’s where a lot of stress comes from — not the tasks themselves, but the uncertainty around what will make the biggest difference.

Clear thinking reduces that uncertainty.

Theme: progress feels good when you can see it

We’re all motivated by visible progress. It’s why children respond to immediate feedback, and why adults love anything that tracks movement: steps, savings, goals, habits.

In school improvement, though, progress can be slow, complex, and hard to spot. And when progress is hard to spot, morale dips. You start to feel busy rather than effective.

So the question becomes: how do we make progress visible without making improvement performative?

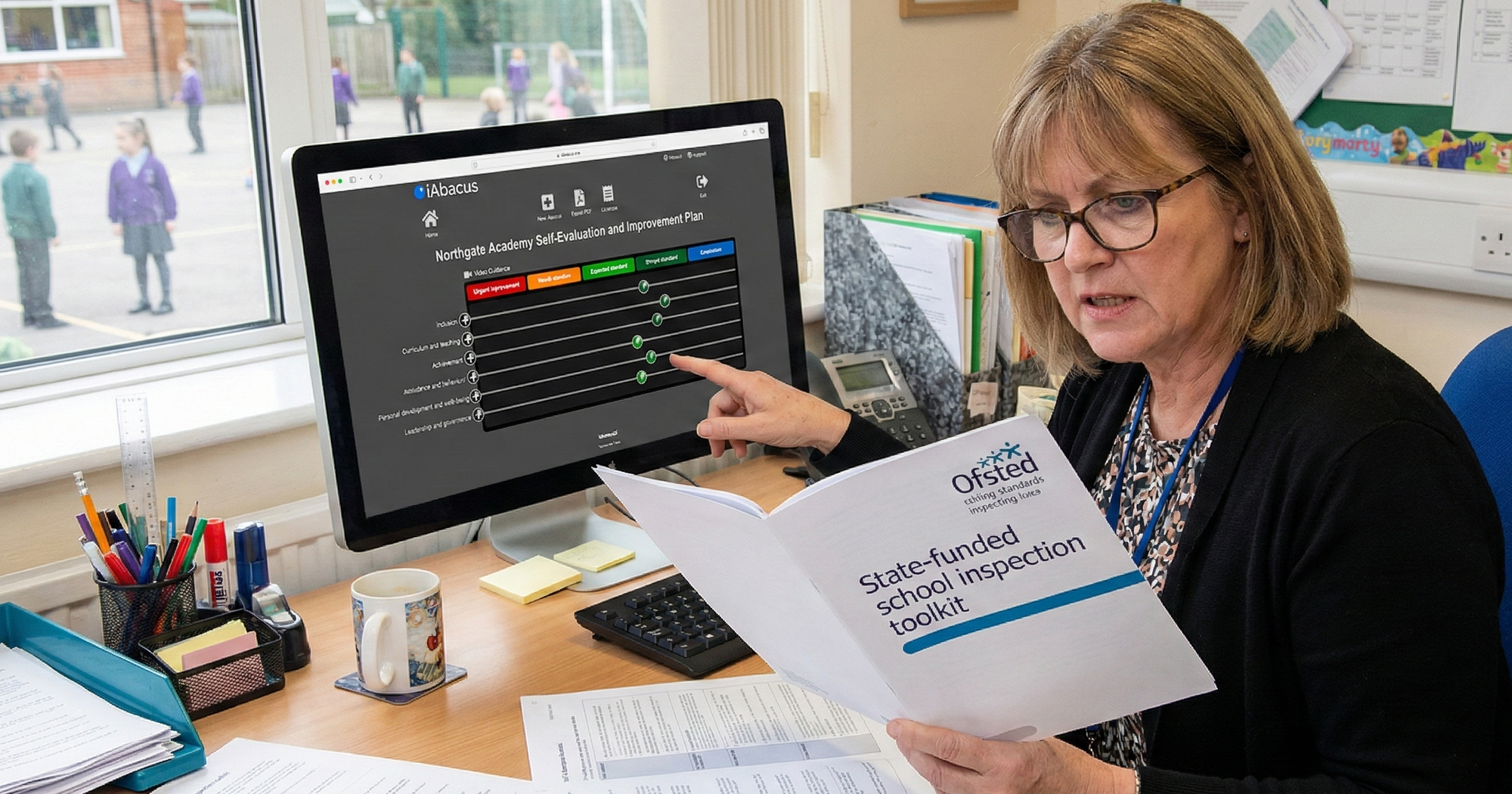

This is where the abacus metaphor is so useful.

A bead is wonderfully honest. No narrative, no defensiveness — just a point in time. And that honesty is what makes progress possible, because you can finally decide what would move it.

The abacus process, in human terms

I’ve always liked the abacus process because it turns improvement into something that’s grounded, shared, and calm. It follows a sequence that works in schools — and honestly, works in any endeavour where you’re trying to get better:

- See where you are

- Understand why you’re there

- Act on what’s actually influencing progress

- Review and move again

Simple doesn’t mean superficial. It means usable — especially in the busy reality of school life.

Let’s break that down.

1) Seeing where you are (with honesty and shared criteria)

Most improvement discussions start with the destination:

“We need to be stronger here.”

“We’ve got to raise standards.”

“We must improve consistency.”

All true. But there’s a subtle trap: if you begin with “where we want to be”, you can skip the most useful step of all — a shared, honest picture of where we are now.

That picture rarely appears fully formed from a spreadsheet. It usually starts with professional nous: the accumulated sense of what it’s like on the ground, how it’s landing for pupils, and where the friction is. That instinct matters — it’s often the earliest, most accurate signal you have.

But instinct on its own can stay a bit foggy. The next move is what brings calm: holding that judgement up against agreed criteria.

When you compare “where we think we are” with a clear set of standards, descriptors, or what good looks like, a few helpful things happen at once:

- you can see how far you’ve already come (and which criteria you genuinely meet)

- you can spot the specific gap to the next level, rather than a vague sense of “not good enough”

- you create a shared language that reduces misunderstanding and defensiveness

In other words, you’re not just judging. You’re locating.

And once a team can say, “We think we’re here — and here’s why, against what we’ve agreed matters,” the conversation changes. People stop speaking in generalities. The unspoken disagreements surface safely because the criteria does some of the heavy lifting. The fog begins to lift.

And that lift, on its own, reduces stress — because it replaces uncertainty with a clear starting point and a believable next step.

2) Understanding why you’re there (where insight lives)

This is the turning point.

The most common mistake in improvement is jumping straight from evaluation to action:

- “Let’s write a plan.”

- “Let’s add monitoring.”

- “Let’s introduce another initiative.”

But action without diagnosis creates activity, not movement. It often makes people busier without making things better.

The better question is:

What’s pushing us forward — and what’s holding us back?

In the abacus process, that becomes a disciplined look at helping factors and hindering factors.

This reframes the work in a more human, more constructive way. Instead of “who’s at fault?” you get “what forces are acting on us right now?”

That’s when teams start thinking clearly again.

3) Tackling the factors that actually shift progress

Once the factors are visible, improvement becomes calmer. You stop trying to fix everything and start making deliberate shifts.

Good actions tend to do one of two things:

- Strengthen a helping factor (protect and amplify what’s already working)

- Reduce a hindering factor (remove friction from the system)

This is how you “move the bead”. Not with grand gestures, but with specific actions that change conditions.

And here’s the rewarding part: when the actions are connected to the factors, progress becomes a result of what you did — not luck, not heroic effort, not another push for compliance.

That’s deeply motivating. Because it restores a sense of agency: we can influence this.

Why this way of thinking reduces stress

Clear thinking doesn’t make the work easy. Schools will always be complex.

But it does remove a major driver of stress: vagueness.

When you can see the factors affecting progress, you no longer have to carry that background anxiety of “something’s not right but I can’t quite name it.”

Instead you get something steadier:

- “This is where we are.”

- “This is why.”

- “These are the two things we’ll shift.”

- “This is what we expect to see change.”

- “This is when we’ll review.”

That turns overwhelm into manageable steps.

And it gives staff something vital at this time of year: a sense that improvement is doable, not just demanded.

A January takeaway for leaders and teams

If you want a useful reset conversation in the first week back, try this simple structure with one priority area:

1) Where are we now?

Keep it honest. Keep it shared.

2) What’s the best evidence that supports that judgement?

Not everything — just the most telling indicators.

3) What are the top two helping factors and top two hindering factors?

Circle only what truly matters.

4) Pick one helping or hindering factor — what can we do next that’s within our control, and that we’ll genuinely follow through on?

The best actions are the ones that survive the realities of the timetable.

That’s enough to create clarity, direction, and a visible next step.

Closing thought: clarity is a form of care

I’ve worked with enough schools to know this: brilliant educators don’t burn out only from hard work. They burn out when hard work feels disconnected from impact.

Clarity reconnects effort to progress.

And when progress is visible — when you can genuinely see the bead move — you don’t just improve outcomes. You improve how it feels to do the work.

That matters in January. And it matters all year.

If this way of thinking feels useful, I’m very happy to walk you through it in your context — not a demo in the usual sense, just a practical conversation about where you are, what’s helping, what’s hindering, and what would genuinely move things forward. If that would help, drop me a message and we’ll find a time. No push, no expectations — the choice is entirely yours. dan@opeus.org