There’s a subtle trap in school improvement.

We build systems to help us improve… and they end up becoming systems that help us prove we’re improving.

It’s not that accountability is wrong. Of course we need clarity for governors, trust boards, and inspection. The problem is when our software is designed primarily to record what’s happening, rather than to help teams cause what happens next.

And when that’s the case, school improvement becomes document production.

iAbacus was built to tackle that exact problem: to keep the rigour, but put the emphasis back where it belongs — on the thinking and actions that actually shift outcomes.

When software is built to record improvement

Most “school improvement platforms” are very good at capturing artefacts:

- the current judgement / RAG rating

- the supporting evidence

- the plan (often as a template)

- a report at the end

In other words: they help you record.

But schools don’t get better because a plan exists. They get better because teams:

- understand what “good” looks like (in plain terms)

- make honest, criterion-referenced judgements

- identify what’s really driving performance (the helps and the barriers)

- commit to actions that are owned, sequenced, and followed through

- revisit, refine, and adjust as reality changes

That’s not documentation. That’s improvement.

And yet plenty of tools stop right at the point where the most important work should begin. You get a neat record of “where we are”… without enough structure to reliably move “where we are” to somewhere better.

Creating improvement requires a cycle, not a snapshot

What I’ve learned (the hard way) is that schools don’t need more places to store information. They need a simple, repeatable process that turns professional insight into action — and then makes progress visible over time.

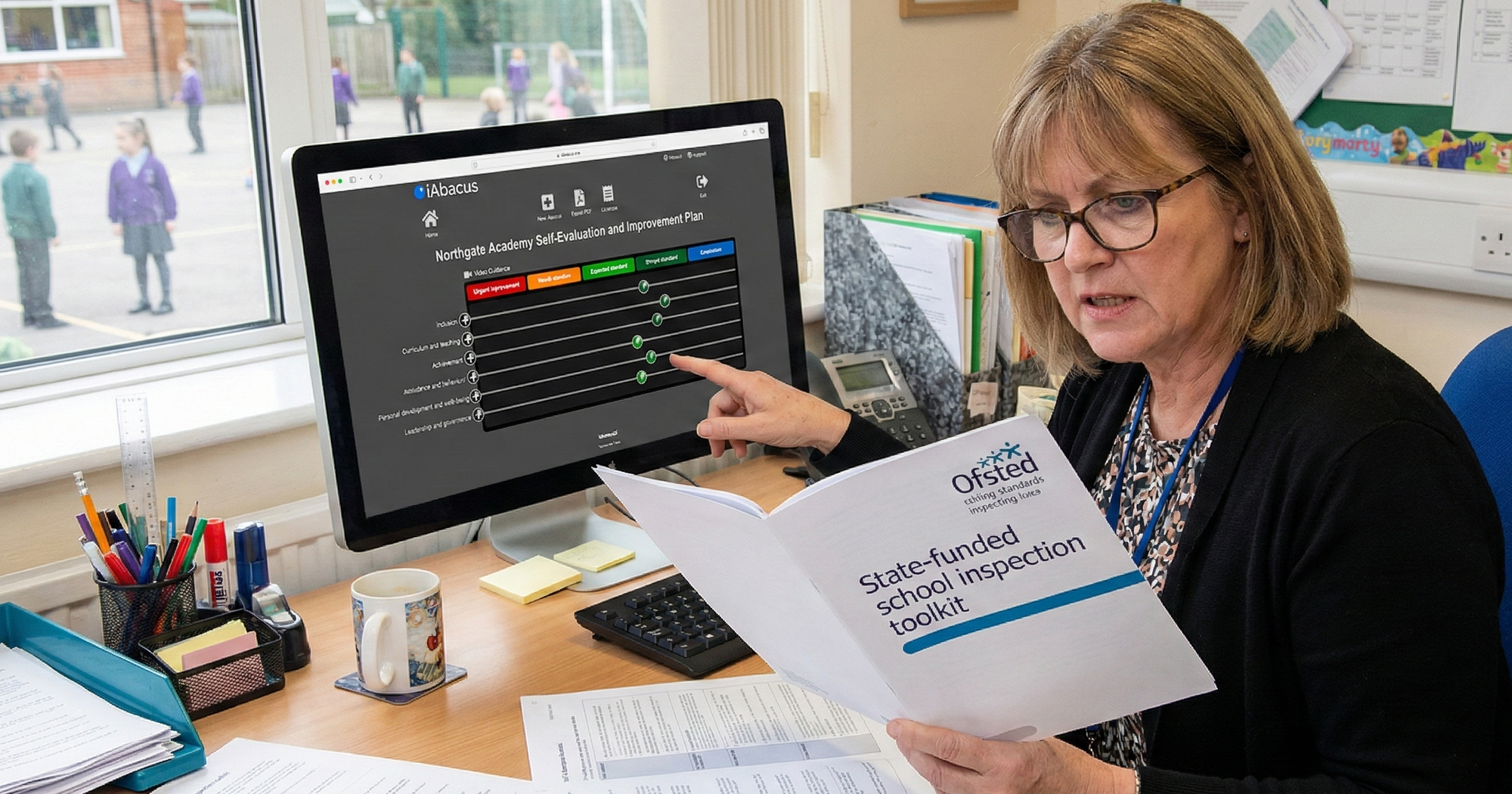

That’s why iAbacus follows a deliberately human sequence:

- Make a judgement (start with your professional insight)

- Check it against criteria (so it’s not just a feeling)

- Add only the evidence that matters (not mountains of “just in case”)

- Analyse helping and hindering factors (the bridge between evaluation and strategy)

- Plan actions with ownership and measures of success

- Re-judge and slide a new bead when improvement happens (with earlier judgements still visible)

That final step is more important than it sounds. It turns improvement into something you can see — not a claim you have to re-write from scratch each term.

The key difference: iAbacus doesn’t “capture” thinking — it guides it

This is where “recording vs creating” becomes real.

iAbacus prompts a team through a set of straightforward questions:

- How well are we doing?

- What’s our evidence?

- What’s helping and hindering success?

- So, what will we do to drive improvement?

That “helping and hindering” stage matters because it stops improvement planning from becoming a wish list.

It forces the conversation from:

“What should we do?”

to:

“What is actually stopping us — and what levers do we have to shift it?”

In the iAbacus model, strategy becomes: strengthen the helping forces and weaken the hindering ones. That’s why plans become sharper, more realistic, and easier to own.

Why most software accidentally gets in the way

When tools are designed primarily for recording, you tend to see the same patterns:

- teams spend time formatting and populating fields rather than diagnosing causes

- evidence becomes excessive (because the tool rewards quantity)

- meetings drift into “updating the system” rather than making decisions

- improvement becomes something written up after the work, not something that shapes the work

And then the tool gets blamed for workload — when really it’s the design philosophy underneath it.

The record should be a by-product of the improvement process — not the main event.

Reporting still matters — but it shouldn’t take your evenings

You still need to communicate clearly with governors, trustees, SLT, and external partners.

So iAbacus includes instant reporting that’s designed to be readable and shareable — without the reformatting dance. You can choose the level of detail and generate a clear report straight from the work you’ve already done.

That’s recording done properly: output that emerges naturally from the process, not output that replaces the process.

The other difference people underestimate: support is part of the product

Most platforms assume implementation is “your problem”.

We don’t.

iAbacus is intentionally delivered as a partnership: onboarding, staff training, INSET, one-to-one sessions, bespoke template design, project support and more — included to help schools actually embed the approach.

Because the goal isn’t for you to have software. It’s for you to have a process that people genuinely use.

If you’re stuck recording improvement, you’re not alone

If your current system is producing documents but not reliably producing change, it’s not because your team lacks commitment.

It’s because improvement doesn’t happen in templates. It happens in cycles of honest evaluation, diagnosis, action, review — and back again.

iAbacus was built to make that cycle simple enough that anyone can own it, and strong enough that leaders can trust it.

Call to action

If you’d like to explore this properly, I’m happy to give you a short personal walkthrough. It’s not a hard-sell demo — just a practical look at how the process would work in your context, with your improvement priorities.

If you’d rather explore first, you can also start with a trial and see how quickly your team can move from “capturing” to “creating”.