There’s a moment most school leaders will recognise.

You’ve booked the session. You’ve built the slides. You’ve carved out precious collegiate time. You’ve framed it carefully: “This is collaborative. This is for us. This is about improving learning.”

And then… one or two voices take over.

Not maliciously. Often they’re well-meaning, confident, articulate colleagues. But the result is the same: the direction of travel is shaped by the dominant few, while everyone else quietly learns the safest strategy is to nod and get through the hour.

The irony is painful: the very process designed to build shared ownership can end up reducing it.

I was reminded of this in a recent conversation with a Scottish headteacher who said something that stopped me in my tracks:

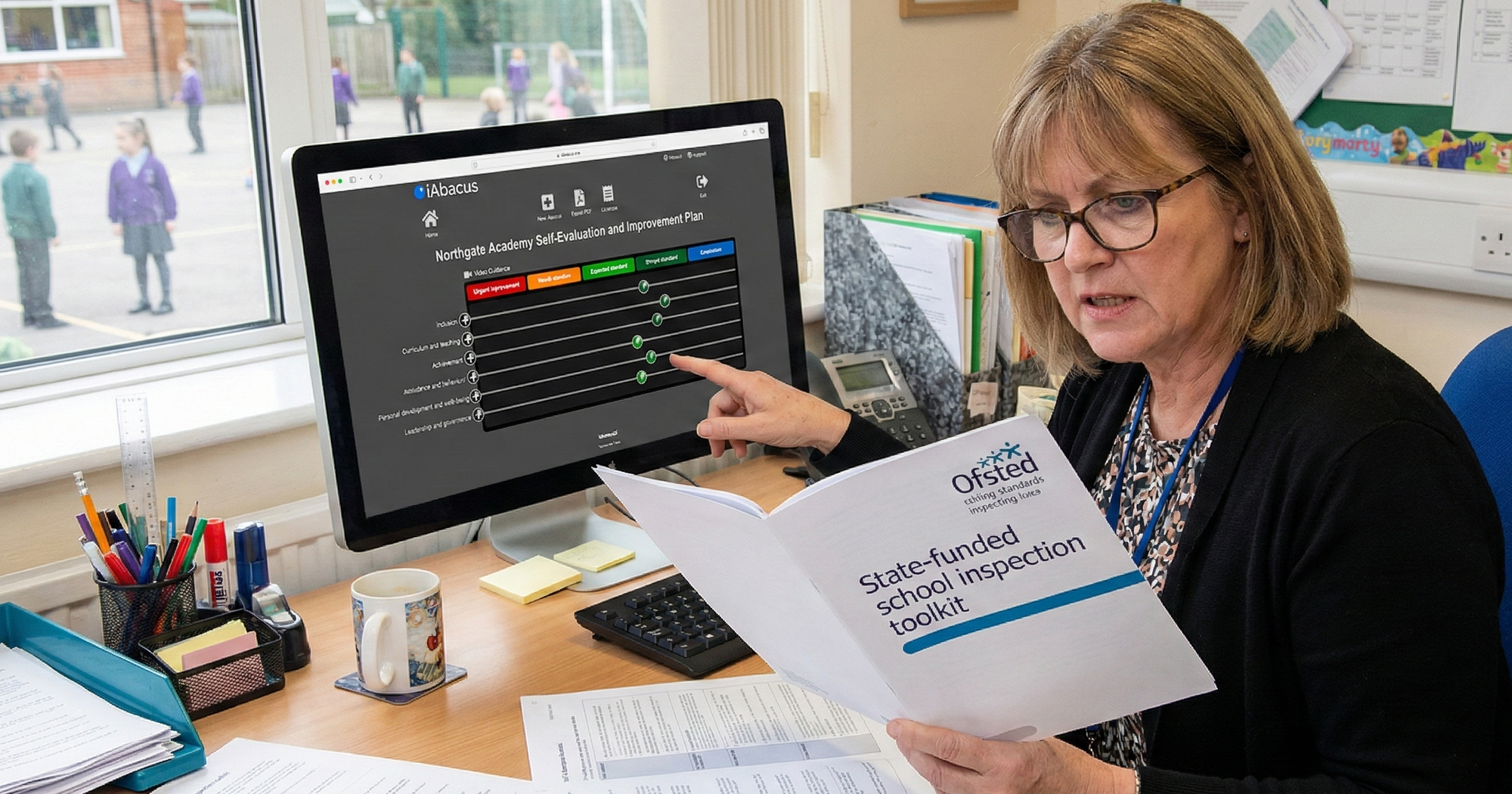

“When people do the old fashioned paper way… you get the dominant person in each group that dictates what is said. iAbacus opens up the voice of everyone.”

He’s right. And it’s worth unpacking why.

The hidden flaw in “collaboration”

Traditional self-evaluation sessions often ask staff to think and speak at the same time, in public, in front of peers, under time pressure.

That’s a perfect recipe for:

- Groupthink (“I’ll go with what’s already been said.”)

- Deference (“I’m not going to contradict them.”)

- Silence (“I don’t want to look negative.”)

- Noise (the loudest voice becomes the agenda)

When leaders later wonder why the plan wasn’t “owned”, it’s sometimes because ownership was never truly invited — only compliance was.

Real collaboration tends to work better when it happens in two stages:

- Private thinking (safe, individual, unhurried)

- Shared meaning-making (collective, moderated, action-focused)

The good news is: you don’t need a new initiative to do this. You just need a cleaner structure.

A simple shift that changes everything

The headteacher I spoke to is juggling what many small-school leaders will recognise: wearing multiple hats, supporting complex needs, keeping learning steady, and preparing for an authority “learning visit” in a matter of weeks.

He put it plainly: he doesn’t want bureaucracy for the sake of it — he wants impact. And he wants staff to feel the work belongs to them.

So we talked through a method that starts with professional judgement (not paperwork), and then uses that judgement to produce a clear, shareable improvement picture.

Here’s the approach.

The “quiet first, then together” model

Step 1: Agree a narrow focus (not the whole framework)

If you try to evaluate everything, you’ll evaluate nothing well.

In this school’s case, the immediate priority wasn’t “all of HGIOS4”. It was the bit that matters most right now:

- Learning and engagement

- Quality of teaching

- Effective use of assessment

- Planning, tracking and monitoring

That’s sensible. Your focus should match your reality.

Step 2: Give every colleague a private space to make a judgement

This is the crucial part.

Instead of a table discussion where confidence becomes currency, each teacher makes their own judgement against agreed criteria:

- Where are we right now?

- What’s the best evidence I can point to?

- What’s helping?

- What’s hindering?

- What action would move this forward?

That structure matters, because it validates professional judgement first, then strengthens it with evidence and analysis.

Step 3: Bring the views together without forcing consensus

Only after individual thinking do you overlay the picture.

When you combine staff perspectives, you get something far more useful than a tidy set of minutes:

- Patterns you can act on

- Variance you can explore

- Strengths you can replicate

- Barriers you can remove

This is where overlaying/stacking multiple evaluations becomes powerful — it turns “lots of opinions” into “one clear picture”, without flattening people’s voices.

Step 4: Build the “polished” version from the shared reality

This is the part leaders often feel they have to do alone, late at night, in Word.

But when you’ve already gathered:

- the judgements,

- the evidence,

- the helping/hindering factors,

- and the suggested actions,

…your final SEF/SIP becomes a synthesis, not a solo performance.

It also becomes much easier to explain — to staff, to governors, to the local authority, to inspectors — because the logic is visible:

judgement → evidence → diagnosis → action.

Why this feels different in the building

What I liked most about the conversation with this headteacher wasn’t the urgency — it was the leadership intent.

He wasn’t looking for a shiny system. He was looking for a way to:

- protect staff time,

- reduce performative paperwork,

- get closer to classroom reality,

- and build genuine ownership.

He also said something else that matters:

“If they don’t own it, they don’t do it.”

That’s not cynicism — it’s experience.

And it’s why this approach works particularly well when:

- you’re leading through turbulence,

- you’re trying to rebuild a culture after instability,

- you’ve got additional support needs rising and capacity stretched,

- and you need the school to move as one, without pretending everyone thinks the same thing.

One practical “starter” you can use next week

If you want to try this without making it a big “launch”, do a single-bead pulse check on one theme:

“Excellent learning: how consistently are we creating high engagement in lessons?”

Keep it tight. Three or four levels. Clear descriptors. One place for evidence. One place for helping/hindering. One action.

You’ll learn more from that in a week than from an hour of round-table discussion — and you’ll do it in a way that respects everyone’s voice.

Because the goal isn’t to create more documentation.

It’s to create more clarity.

And in schools, clarity is kindness.

If you want to test the approach without making it a “thing”, start with a single-bead pulse check on one priority (teaching & learning, behaviour, attendance — whatever matters most right now). If you’d like, I’ll share a simple starter template you can copy and run next week.